Part 2 of “Grassroots Recycling in Saigon”

The text message said to be ready at 4:30am at my street corner and I would be picked up for the drive to the plastics recycling center. I had been wanting to visit the site for this article and thinking that we had hours of travel ahead, didn’t question the time.

Walking up the street, surrounded by stillness, I reached the corner rendezvous spot 15 minutes early. But I was not alone in the night. A few itinerant recycling collectors peddled their carts along Đào Trí Street. I was then caught like a deer in the headlights of the flatbed trucks setting out with their container loads from the port; their beams piercing the ink-blue sky. A taxi driver stopped for a smoke. And the lone jogger turning into the block was more startled to see another person at this time of night. “Beats the morning heat” he shouted, as to mask any lingering fear.

Right on time their truck lights flashed and Hai and Su’ beckoned me into the cab. I settled in, closed my eyes anticipating a quiet drive. Yet Hai drove the truck with abandon, while a pair of speakers rigged on the dashboard blared soulful Vietnamese ballads and then 80’s Western rock tunes. Certainly couldn’t fall asleep. It was reminiscent of my fondness for working and driving in the middle of the night.

Once off the main highway in Binh Chanh District, we bounced along rutted, one-lane rural roads which had probably not seen a grader in years.

Not even an hour had passed since departing and Hai parked the truck behind one other in front of a locked tin gate. “C’mon, coffee time” he shouted as he swung the truck door open. Walking 50 meters to a roadside store, the shopkeeper brought out comfortable folding chairs and iced coffees [cà phê đá] for the slowly expanding circle of drivers and a few of the plant workers now gathering.

I now understood the rationale for the pre-dawn start. Trucks are allowed in only one at a time to unload and the process takes around one hour per truck. It’s best to arrive early and avoid the long queue.

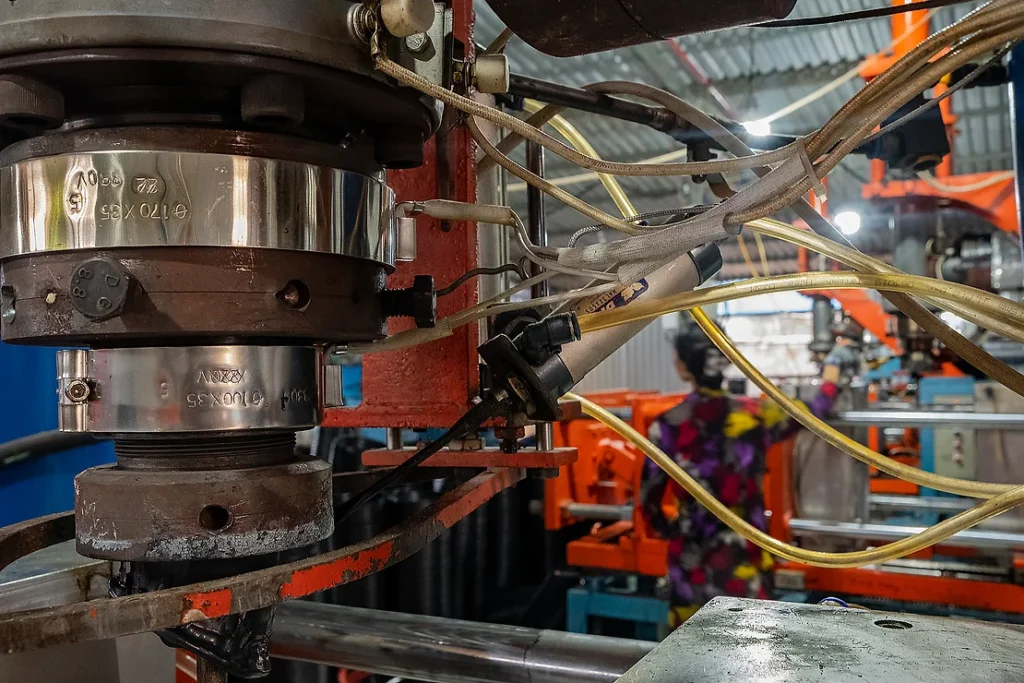

A muted orange dawn was now inching over the sky. It was just after 7am that I accompanied Hai into the first building which produced planter pots from recycled plastic. The technician was just firing up the heating unit, as Hai showed me the rather simple looking but efficient process. After sorting and grinding the plastic into small chips, they are fed into a tube, then super-heated and extruded into long strands. These spaghetti-like ribbons are then passed through a cooling pool and at the other end, are chopped into small pellets. In an adjacent room, the pellets were being injected into four large molding machines which produced the pots. At a final station, drainage holes were punched into the bottom of each planter.

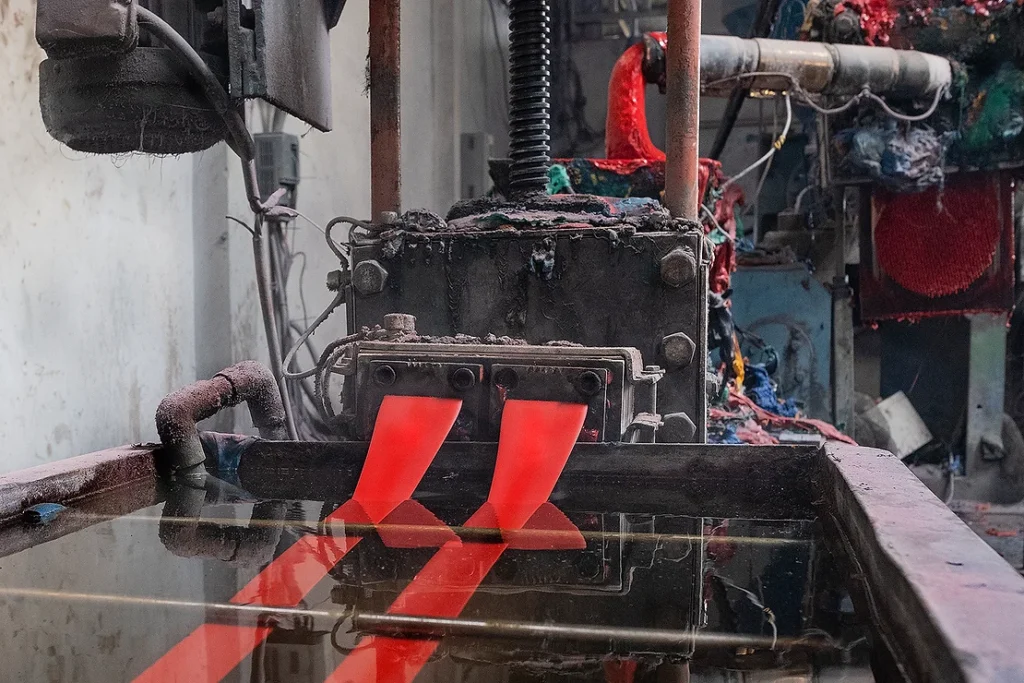

We then proceeded to another building, where I viewed ground red plastic components being heated and converted into a molten, dough-like stream which was then extruded into flat ribbons. The ribbons then passed through a ‘Rube Goldberg-like’ series of spools and posts until they were flattened and spun into a master roll of colored strapping tape.

While these areas hummed with a quiet efficiency, the most energetic was a buzz of activity in the sorting area. Plastics are first grouped by type and then by color. Women sat cross-legged, every few meters, with large Crayola colored tubs in front of them. A steady chatter pervaded the room, but did not deter the process. With surgical precision, they peeled labels and tossed the now bare containers into color-coded bins. Belying his age and slight build, an elderly gentleman [người đàn ông cao tuổi] hoisted sacks of colored plastic onto wheel barrels for the trip next door to the shredding area.

Just outside this building the trucks are backed into the receiving area where the contents are off-loaded, weighed and then stacked. A growing fortress, with walls of baled plastics, was now enveloping us.

Through an interpreter, I questioned a couple of the women on how they felt about their jobs as part of the broader recycling effort in Saigon. “For us, it’s steady work. There doesn’t seem to be a shortage of plastic to repurpose.” Another added, “As long as people keep using these products, our income is secure.”

Since China’s ban on plastic imports took effect in January 2018, much of that by-product was diverted to SE Asian countries such as here, in Vietnam. Coupled with growing urbanization and the mania for single-use products, plastic accounts for between 12% and 16% of all waste in and dumps in Saigon, according to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. It is estimated that these types of plastics will take a few hundred years to breakdown. And what doesn’t get recycled or placed in landfill, inevitably gets dumped into the ocean.

Part of the plastic issue that has root here, is that the material is seen as a status symbol. In the rush to modernity, locals embrace plastic as a sign of upward mobility. As an example, Saigoneers love their fresh smoothies and coffee drinks. What is not realized, is the scant percentage of the single-use plastic drinking cups, dome covers, straws, wrappers, and holders that are recycled.

And that’s just one product. Walking through a supermarket, one sees the myriad number of products that rely on plastic packaging or are made from molded plastic [i.e. rolling mop pails]. Wasteful packaging is another sticking point. A memory card purchased for my camera, came encapsulated in enough plastic packaging that could have held four more items in the same box.

An acquaintance of mine, who preferred not to be named, worked for ten years as an environmental lawyer in her native Brazil, then took a two-year hiatus to travel and teach in SE Asia. “I always try to teach and raise the awareness level of students of the need to use sustainable practices in everyday life. It’s hard to undo years of modernization and unchecked growth without realizing the longer-term consequences. There are a number of positive initiatives being undertaken here, but it will only be through education, that we can start raising the awareness levels, especially of the younger generations.”

I spoke again with Hung and Hai and asked how they saw their role in the overall scope of recycling effort.

Hai replied, “We are in a bridge role between the local collector and the larger recycling companies. If the individuals or small recycling companies didn’t have a resource like us, I doubt they would know where to buy the materials from.”

Hung added that they envision 60-70 years of growing business. “It’s a culture of the user who has to learn to separate and recycle the various plastics. It’s not like Japan or Taiwan. There is minimal segregating waste at the source here, so it becomes more labor intensive and ultimately costlier. It will need a massive awareness campaign and mind-shift to get people to change their ways when it comes to recycling.”

Text and all photographs copyright in perpetuity by Jim Selkin